I will post information about the

Mein Kampf in the Arabic Language from Wikipedia.

|

|

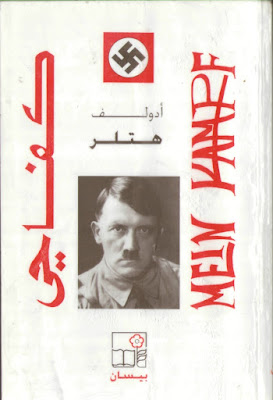

The front cover of the 1995 edition of Mein

Kampf issued by Bisan Publishers and sold in London. This edition was a

republishing of a translation first published in 1963.

|

Mein Kampf (English:

My Struggle, Arabic: كفاحي kifāḥī), Adolf

Hitler's 900-page autobiography outlining his political views, has been

translated into Arabic a number of times since the early 1930s.

Translations

Translations

between 1934 and 1937

The

first attempts to translate Mein Kampf into Arabic were extracts in

various Arab newspapers in the early 1930s. Journalist and Arab nationalist Yunus

al-Sabawi published translated extracts in the Baghdadi newspaper al-Alam

al-Arabi, alarming the Baghdadi Jewish community. Lebanese

newspaper al-Nida

also separately published extractions in 1934. The German consulate denied it

had been in touch with al-Nida for these initial translations.

Whether

a translation published by the Nazi regime would be allowed, ultimately

depended on Hitler. Fritz Grobba,

the German ambassador to the Kingdom of Iraq, played a key role in

urging the translation. The largest issue was the book's racism. Grobba

suggested modifying the text "in ways that correspond to the sensitivities

of the race conscious Arabs", such as changing "anti-Semitic" to

"anti-Jewish", "bastardized" to "dark" and toning

down arguments for the supremacy of the "Aryan race".

Hitler

wanted to avoid allowing any modifications, but accepted the Arabic book

changes after two years. Grobba sent 117 clippings from al-Sabawi's

translations, but Bernhard

Moritz, an Arabist consultant for

the German Government who was also fluent in Arabic, said the proposed

translation was incomprehensible and rejected it. This particular attempt ended

at that time.

Subsequently,

the Ministry of Propaganda of Germany decided to proceed with the translation

via the German bookshop Overhamm in Cairo. The translator was Ahmad

Mahmud al-Sadati, a Muslim and the publisher of one of the first

Arabic books on National Socialism:

Adolf Hitler, za'im al-ishtirakiya al-waṭaniya ma' al-bayan lil-mas'ala

al-yahudiya. "(A.H., leader of National Socialism, together with an

explanation of the Jewish question)." The manuscript was presented for Dr.

Moritz's review in 1937. Once again, he rejected the translation, saying it was

incomprehensible.

1937

translation

Al-Sadati published his translation

of Mein Kampf in Cairo in 1937 without German approval. According to Yekutiel

Gershoni and James Jankowski, the Sadati

translation did not receive wide circulation. However, local Arab weekly Rose

al-Yūsuf published Hitler's quote from the book on Egyptians, that they are

a "decadent people composed of cripples." The quote raised angry

responses. Hamid Maliji, an Egyptian

attorney wrote:

Arab friends:...The Arabic copies of Mein Kampf distributed in the Arab world do not conform to the original German edition since the instructions given to Germans regarding us have been removed. In addition, these excerpts do not reveal his [Hitler's] true opinion of us. Hitler asserts that Arabs are an inferior race, that the Arabic heritage has been pillaged from other civilizations, and that Arabs have neither culture nor art, as well as other insults and humiliations that he proclaims concerning us.— Hamid Maliji

Another

commentator, Niqula Yusuf, denounced the

militant nationalism of Mein Kampf as "chauvinist".

The

Egyptian journal al-Isala stated that "it

was Hitler's tirades in Mein Kampf that turned anti-Semitism into a

political doctrine and a program for action". al-Isala rejected

Nazism in many publications.

Attempts

at revision

A

German diplomat in Cairo suggested that instead of deleting the offending

passage about Arabs, it would be better to add to the introduction a statement

that "Egyptian

people" were differentially developed and that the Egyptians standing

at a higher level themselves do not want to be placed on the same level with

their numerous backward fellow Egyptians.'" Otto von Hentig, a staff

member of the German foreign ministry suggested that the translation should be

rewritten in a style "that every Muslim understands: the Koran," to give

it a more sacred tone. He said that "a truly good Arabic translation would

meet with extensive sympathy in the whole Arabic speaking world from Morocco to India."

Eventually the translation was sent to Arab nationalism advocate Shakib

Arslan. Arslan, who lived in Geneva, Switzerland, was an editor of La Nation arabe, an

influential Arab nationalist paper. He also was a confidant of Haj Aminal-Husseini, a Palestinian Arab

nationalist and Muslim leader in the British Mandate of Palestine, who met

with Hitler.

Arslan's

960 page translation was almost completed when the Germans requested to

calculate the cost of the first 10,000 copies to be printed with "the

title and back of the flexible cloth binding... lettered in gold." On 21

December 1938 the project was rejected by the German ministry of

propaganda because of the high cost of the projected publication.

1963

translation

A

new translation was published in 1963, translated by Luis al-Haj, a Nazi war criminal originally named Luis Heiden

who fled to Egypt after World War II. The book was republished in 1995 by Bisan Publishers in Beirut.

According to a September 8, 1999, Agence France Presse report, Mein Kampf

ranked sixth on the bestseller list compiled by Dar el-Shuruq bookshop in Ramallah, with

sales of less than 10 copies a week. The bookshop owner attributed its

popularity to its having been unavailable in the Palestinian territories due to

an Israeli ban, and the Palestinian National Authority

recently allowing it to be sold. As of 2002, newsdealers on Edgware

Road in central London, an area with a large Arab population, were selling

the translation. In 2005, the Intelligence and

Terrorism Information Center, an Israeli think tank, confirmed the

continued sale of the Bisan edition in bookstores in Edgware Road. In 2007 an Agence France-Presse reporter interviewed a

bookseller at the Cairo International Book Fair who

stated he had sold many copies of Mein Kampf.

Role

in Nazi propaganda

One

of the leaders of the Syrian Ba'ath Party, Sami

al-Jundi, wrote: "We were racialists, admiring Nazism, reading its

books and the source of its thought... We were the first to think of

translating Mein Kampf." This statement was incorrect. There were

other translations or partial translations of the book well before 1939.

According

to Jeffrey

Herf, "To be sure, the translations of Hitler's Mein Kampf and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

into Arabic were important sources of the diffusion of Nazi ideology and

anti-Semitic conspiracy thinking to Arab and Muslim intellectuals. Although

both texts were available in various Arabic editions before the war began, they

played little role in the Third Reich's Arab propaganda."

Mein Kampf and Arab nationalism

Mein Kampf

has been pointed to as an example of the influence of Nazism for Arab

nationalists. According to Stefan Wild of the University of

Bonn, Hitler's philosophy of National Socialism – of a state headed by a

single, strong, charismatic leader with a submissive and adoring people – was a

model for the founders of the Arab nationalist movement. Arabs favored Germany

over other European powers, because "Germany was seen as having no direct

colonial or territorial ambitions in the area. This was an important point of

sympathy", Wild wrote. They also saw German nationhood—which preceded

German statehood—as a model for their own movement.

In

October 1938, anti-Jewish treatises that included extracts from Mein Kampf

were disseminated at an Islamic parliamentarians' conference "for the

defense of Palestine" in Cairo.

During

the Suez war

In

a speech to the United Nations immediately following the Suez Crisis in 1956, Israeli Prime Minister

Golda Meir claimed that the Arabic

translation of Mein Kampf was found in Egyptian

soldiers' knapsacks. In the same speech she also described Gamal Abdel Nasser

as a "disciple of Hitler who was determined to annihilate Israel".

After the war, David Ben-Gurion

likened Nasser's Philosophy

of the Revolution to Hitler's Mein Kampf, a comparison

also made by French Prime Minister Guy Mollet, though Time Magazine at the

time discounted this comparison as "overreaching". "Seen from

Washington and New York, Nasser was not Hitler and Suez was not the

Sinai," writes Philip Daniel Smith, dismissing the comparison. According

to Benny Morris, Nasser however had not

publicly called for the destruction of Israel until after the war, but other

Egyptian politicians preceded him in this regard. The second generation of

Israeli history textbooks included a photograph of Hitler's Mein Kampf

found at Egyptian posts during the war. Elie

Podeh writes that the depiction is "probably genuine", but

that it "served to dehumanize Egypt (and especially Nasser) by associating

it with the Nazis."

No comments:

Post a Comment