As I became a Pro-Life person, I

will support the March for Life in Washington D.C every year on January 22. Let

us learn about Roe V. Wade and Doe V. Bolton from Wikipedia.

|

|

Protestors at the 2009 March for Life rally against

Roe v. Wade

|

|

|

Rep. Albert Wynn

(left) joins Gloria Feldt (right), President of the Planned

Parenthood Federation of America, on the steps of the Supreme Court, to rally

in support of the pro-choice movement on the Anniversary of Roe v. Wade

|

INTERNET SOURCE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roe_v._Wade

Argued December 13,

1971

Reargued October 11, 1972 Decided January 22, 1973 |

|||||||

Full case name

|

Jane

Roe, et al. v. Henry Wade, District Attorney of Dallas County

|

||||||

Citations

|

93 S. Ct. 705; 35 L. Ed. 2d 147; 1973

U.S. LEXIS 159

|

||||||

Prior history

|

Judgment for plaintiffs, injunction denied, 314 F. Supp. 1217

(N.D. Tex. 1970); probable jurisdiction noted, 402 U.S. 941 (1971); set

for reargument, 408 U.S. 919 (1972)

|

||||||

Subsequent history

|

Rehearing denied, 410 U.S. 959

(1973)

|

||||||

Argument

|

|||||||

Reargument

|

|||||||

Holding

|

|||||||

Texas law making it

a crime to assist a woman to get an abortion violated her due process rights.

U.S. District

Court for the Northern District of Texas affirmed in part, reversed in

part.

|

|||||||

Court membership

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

Case opinions

|

|||||||

Majority

|

Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas,

Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell

|

||||||

Concurrence

|

Burger

|

||||||

Concurrence

|

Douglas

|

||||||

Concurrence

|

Stewart

|

||||||

Dissent

|

White, joined by Rehnquist

|

||||||

Dissent

|

Rehnquist

|

||||||

Laws applied

|

|||||||

Roe v. Wade,

410 U.S. 113 (1973), is a

landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court on the issue of abortion.

Decided simultaneously with a companion case, Doe v. Bolton, the Court

ruled 7–2 that a right to privacy under the due process clause of the 14th

Amendment extended to a woman's decision to have an abortion, but that right

must be balanced against the state's two legitimate interests in regulating

abortions: protecting prenatal life and protecting women's health. Arguing that

these state interests became stronger over the course of a pregnancy, the Court

resolved this balancing test by tying state regulation of abortion to the

trimester of pregnancy.

The

Court later rejected Roe's trimester framework, while affirming Roe's

central holding that a person has a right to abortion until viability. The Roe

decision defined "viable" as being "potentially able to live outside

the mother's womb, albeit with artificial aid", adding that viability

"is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier,

even at 24 weeks."

In

disallowing many state and federal restrictions on abortion in the United States,

Roe v. Wade prompted a national debate that continues today, about

issues including whether and to what extent abortion should be legal, who

should decide the legality of abortion, what methods the Supreme Court should

use in constitutional adjudication, and what the role should be of religious

and moral views in the political sphere. Roe v. Wade reshaped national

politics, dividing much of the United States into pro-choice and pro-life

camps, while activating grassroots movements on both sides.

Background

History

of abortion laws in the United States

According

to the Court, "the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a

majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage." In 1821,

Connecticut passed the first state statute criminalizing abortion. Every state

had abortion legislation by 1900. In the United States, abortion was sometimes

considered a common law crime, though Justice Blackmun would conclude that the

criminalization of abortion did not have "roots in the English common-law

tradition."

Prior

history of the case

In

June 1969, Norma L. McCorvey discovered she was pregnant with her third child.

She returned to Dallas, Texas, where friends advised her to assert falsely that

she had been raped in order to obtain a legal abortion (with the understanding

that Texas law allowed abortion in cases of rape and incest). However, this

scheme failed because there was no police report documenting the alleged rape.

She attempted to obtain an illegal abortion, but found the unauthorized site

had been closed down by the police. Eventually, she was referred to attorneys

Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington. (McCorvey would give birth before the case

was decided.)

In

1970, Coffee and Weddington filed suit in a U.S. District Court in Texas on

behalf of McCorvey (under the alias Jane Roe). The defendant in the case was

Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade,

representing the State of Texas. McCorvey was no longer claiming her pregnancy

was the result of rape, and later acknowledged that she had lied about having

been raped. "Rape" is not mentioned in the judicial opinions in this

case.

The

district court ruled in McCorvey's favor on the legal merits of her case, but

declined to grant an injunction against the enforcement of the laws barring

abortion. The district court's decision was based upon the 9th Amendment, and

the court relied upon a concurring opinion by Justice Arthur

Goldberg in the 1965 Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut, finding in the

decision for a right to privacy.

Before

the Supreme Court

Roe v. Wade

reached the Supreme Court on appeal in 1970. The Justices delayed taking action

on Roe and a closely related case, Doe v. Bolton, until they

decided Younger v. Harris, as they felt that the

appeals raised difficult questions on judicial jurisdiction, and United States v. Vuitch, where they

considered the constitutionality of a District of Columbia statute that

criminalized abortion except where the mother's life or health was endangered.

In Vuitch, the Court narrowly upheld the statute, though in doing so, it

treated abortion as a medical procedure and stated that the physician must be

given room to determine what suffices as a danger to (physical or mental)

health. The day after they announced their decision in Vuitch, they

voted to hear both Roe and Doe.

Arguments

were scheduled by the full Court for December 13, 1971. Before the Court could

hear the oral arguments, Justices Black and

Harlan retired. Chief Justice Burger

asked Justices Stewart and Blackmun to determine whether Roe

and Doe, among others, should be heard as scheduled. According to

Blackmun, Stewart felt that the cases were a straightforward application of Younger

v. Harris and recommended that the Court move forward as scheduled.

In

his opening argument in defence of the abortion restrictions, Jay Floyd made a

joke that was later described as the "Worst Joke in Legal History".

Appearing against two female lawyers, Floyd began, "Mr. Chief Justice and

may it please the Court. It’s an old joke, but when a man argues against two

beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word." His

remark was met with cold silence; one observer thought that Chief Justice

Burger "was going to come right off the bench at him. He glared him

down".

Following

a first round of arguments, all seven Justices tentatively agreed that the law

should be struck down, but for varying reasons. Burger assigned the role of

writing the Court's opinion in Roe (as well as Doe) to Blackmun,

who began drafting a preliminary opinion that emphasized what he saw as the

Texas law's vagueness. Justices Rehnquist and Powell joined the Supreme Court

too late to hear the first round of arguments. Additionally, Blackmun felt that

his opinion was an inadequate reflection of his liberal colleagues' opinions.

In May 1972, Blackmun proposed that the case be reargued. Justice Douglas

threatened to write a dissent from the reargument order (he and the other

liberal Justices were suspicious that Rehnquist and Powell would vote to uphold

the statute), but was coaxed out of the action by his colleagues, and his

dissent was merely mentioned in the reargument order without further statement

or opinion. The case was reargued on October 11, 1972. Weddington continued to

represent Roe, and Texas Assistant Attorney General Robert C. Flowers

stepped in to replace Jay Floyd for Texas.

Blackmun

continued work on his opinions in both cases over the summer recess, despite

the fact that there was no guarantee that he would be assigned to write the

opinions again. Over the recess, Blackmun spent a week researching the history

of abortion at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he had worked in the 1950s.

After the Court heard the second round of arguments, Powell stated that he

would agree with Blackmun's conclusion but pushed for Roe to be the lead

of the two abortion cases being considered. Powell also suggested that the

Court strike down the Texas law on privacy grounds. White was unwilling to sign

on to Blackmun's opinion, and Rehnquist had already decided to dissent.

Supreme

Court decision

The

Court issued its decision on January 22, 1973, with a 7-to-2 majority vote in

favor of Roe. Burger and Douglas' concurring opinions and White's dissenting

opinion were issued along with the Court's opinion in Doe v. Bolton

(announced on the same day as Roe v. Wade). The Court deemed abortion a

fundamental right under the United States Constitution, thereby subjecting all

laws attempting to restrict it to the standard of strict scrutiny.

Right

to privacy

The

Court declined to adopt the district court's Ninth Amendment rationale, and

instead asserted that the "right of privacy, whether it be founded in the

Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state

action, as we feel it is, or, as the district court determined, in the Ninth

Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a

woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy." Douglas, in

his concurring opinion in the companion case Doe v. Bolton, stated more

emphatically that, "The Ninth Amendment obviously does not create

federally enforceable rights."

The

Court asserted that the government had two competing interests – protecting the

mother's health and protecting the "potentiality of human life".

Following its earlier logic, the Court stated that during the first trimester,

when the procedure is more safe than childbirth, the decision to abort must be

left to the mother and her physician. The State has the right to intervene

prior to fetal viability only to protect the health of the

mother, and may regulate the procedure after viability so long as there is

always an exception for preserving maternal health. The Court additionally

added that the primary right being preserved in the Roe decision was

that of the physician's right to practice medicine freely absent a compelling

state interest – not women's rights in general. The Court explicitly rejected a

fetal "right to life" argument.

The

Justices had discussed the trimester framework extensively. Powell had

suggested that the point where the State could intervene be placed at

viability, which Marshall supported as well. Blackmun wrote of the majority

decision he authored: "You will observe that I have concluded that the end

of the first trimester is critical. This is arbitrary, but perhaps any other

selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary."

Douglas preferred the first trimester line, while Stewart said the lines were

"legislative" and wanted more flexibility and consideration paid to

the state legislatures, though he joined Blackmun's decision. Brennan proposed

abandoning frameworks based on the age of the fetus and instead allowing states

to regulate the procedure based on its safety for the mother.

Justiciability

An

aspect of the decision that attracted comparatively little attention was the

Court's disposition of the issues of standing and mootness. Under the

traditional interpretation of these rules, Jane Roe's appeal was

"moot" because she had already given birth to her child and thus

would not be affected by the ruling; she also lacked "standing" to

assert the rights of other pregnant women. As she did not present an "actual

case or controversy" (a grievance and a demand for relief), any opinion

issued by the Supreme Court would constitute an advisory opinion, a practice

forbidden by Article III of the United States Constitution.

The

Court concluded that the case came within an established exception to the rule;

one that allowed consideration of an issue that was "capable of

repetition, yet evading review". This phrase had been coined in 1911 by

Justice Joseph McKenna. Blackmun's opinion quoted McKenna,

and noted that pregnancy would normally conclude more quickly than an appellate

process: "If that termination makes a case moot, pregnancy litigation

seldom will survive much beyond the trial stage, and appellate review will be

effectively denied."

Dissents

Justices

Byron R. White and William H. Rehnquist wrote emphatic dissenting opinions in

this case. White wrote:

I find nothing in the language or history of the Constitution to support the Court's judgment. The Court simply fashions and announces a new constitutional right for pregnant women and, with scarcely any reason or authority for its action, invests that right with sufficient substance to override most existing state abortion statutes. The upshot is that the people and the legislatures of the 50 States are constitutionally disentitled to weigh the relative importance of the continued existence and development of the fetus, on the one hand, against a spectrum of possible impacts on the woman, on the other hand. As an exercise of raw judicial power, the Court perhaps has authority to do what it does today; but, in my view, its judgment is an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review that the Constitution extends to this Court.

White

asserted that the Court "values the convenience of the pregnant mother

more than the continued existence and development of the life or potential life

that she carries." Despite White suggesting he "might agree"

with the Court's values and priorities, he wrote that he saw "no

constitutional warrant for imposing such an order of priorities on the people

and legislatures of the States." White criticized the Court for involving

itself in this issue by creating "a constitutional barrier to state

efforts to protect human life and by investing mothers and doctors with the

constitutionally protected right to exterminate it." He would have left

this issue, for the most part, "with the people and to the political

processes the people have devised to govern their affairs."

Rehnquist

elaborated upon several of White's points, by asserting that the Court's

historical analysis was flawed:

To reach its result, the Court necessarily has had to find within the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment a right that was apparently completely unknown to the drafters of the Amendment. As early as 1821, the first state law dealing directly with abortion was enacted by the Connecticut Legislature. By the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, there were at least 36 laws enacted by state or territorial legislatures limiting abortion. While many States have amended or updated their laws, 21 of the laws on the books in 1868 remain in effect today.

From

this historical record, Rehnquist concluded that, "There

apparently was no question concerning the validity of this provision or of any

of the other state statutes when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted."

Therefore, in his view, "the drafters did not intend to have the

Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the power to legislate with

respect to this matter."

Reception

Political

The

most prominent organized groups that mobilized in response to Roe are

the National Abortion Rights Action League and

the National Right to Life Committee.

Support

Advocates

of Roe describe it as vital to the preservation of women's rights,

personal freedom, and privacy. Denying the abortion right has been equated to

compulsory motherhood, and some scholars (not including any member of the

Supreme Court) have argued that abortion bans therefore violate the Thirteenth

Amendment:

When women are compelled to carry and bear children, they are subjected to 'involuntary servitude' in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment….[E]ven if the woman has stipulated to have consented to the risk of pregnancy, that does not permit the state to force her to remain pregnant.

Some

opponents of abortion maintain that personhood begins at fertilization (also

referred to as conception), and should therefore be protected by the

Constitution; the dissenting justices in Roe instead wrote that

decisions about abortion "should be left with the people and to the

political processes the people have devised to govern their affairs."

The

majority opinion allowed states to protect "fetal life after

viability" even though a fetus is not "a person within the meaning of

the Fourteenth Amendment". Supporters of Roe contend that the

decision has a valid constitutional foundation, or contend that justification

for the result in Roe could be found in the Constitution but not in the

articles referenced in the decision.

Opposition

Every

year, on the anniversary of the decision, opponents of abortion march up

Constitution Avenue to the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., in the

March for Life. Around 250,000 people have attended the march until 2010.

Estimates put both the 2011 and 2012 attendances at 400,000 each, and the 2013

March for Life drew an estimated 650,000 people.

Opponents

of Roe have asserted that the decision lacks a valid constitutional

foundation. Like the dissenters in Roe, they have maintained that the

Constitution is silent on the issue, and that proper solutions to the question

would best be found via state legislatures and the legislative process, rather

than through an all-encompassing ruling from the Supreme Court.

A

prominent argument against the Roe decision is that, in the absence of

consensus about when meaningful life begins, it is best to avoid the risk of

doing harm.

In

response to Roe v. Wade, most states enacted or attempted to enact laws

limiting or regulating abortion, such as laws requiring parental consent for

minors to obtain abortions, parental notification laws, spousal mutual consent

laws, spousal notification laws, laws requiring abortions to be performed in

hospitals but not clinics, laws barring state funding for abortions, laws

banning intact dilation and extraction (also known as partial-birth abortion),

laws requiring waiting periods before abortion, and laws mandating women read

certain types of literature and watch a fetal ultrasound before undergoing an

abortion. Congress in 1976 passed the Hyde Amendment, barring federal funding

of abortions (except in the cases of rape, incest, or a threat to the life of

the mother) for poor women through the Medicaid program. The Supreme Court

struck down several state restrictions on abortions in a long series of cases

stretching from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s, but upheld restrictions on

funding, including the Hyde Amendment, in the case of Harris v. McRae

(1980).

Perhaps

the most notable opposition to Roe comes from Roe herself; in 1995,

Norma L. McCorvey revealed that she became pro-life and is now a vocal opponent

of abortion.

Legal

Harry

Blackmun, who authored the decision, became inexorably attached to the

decision. Despite his initial reluctance, he eventually became the decision's

chief champion and protector during his later years on the Court. Others have

joined him in support of Roe, including Judith Jarvis Thomson, who

before the decision had offered an influential defense of abortion.

Liberal

and feminist legal scholars have had various reactions to Roe, not

always giving the decision unqualified support. One reaction has been to argue

that Justice Blackmun reached the correct result but went about it the wrong

way. Another reaction has been to argue that the end achieved by Roe

does not justify the means.

Justice

John Paul Stevens, while agreeing with the

decision, has suggested that it should have been more narrowly focused on the

issue of privacy. According to Stevens, if the decision had avoided the

trimester framework and simply stated that the right to privacy included a

right to choose abortion, "it might have been much more acceptable"

from a legal standpoint. His colleague Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had, before joining the

Court, criticized the decision for terminating a nascent movement to liberalize

abortion law through legislation. Ginsburg has also faulted the approach taken

by the Court in the decision for being "about a doctor's freedom to

practice his profession as he thinks best.... It wasn't woman-centered. It was

physician-centered.” Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox wrote: "[Roe’s]

failure to confront the issue in principled terms leaves the opinion to read

like a set of hospital rules and regulations.... Neither historian, nor layman,

nor lawyer will be persuaded that all the prescriptions of Justice Blackmun are

part of the Constitution."

In

a highly cited 1973 article in the Yale Law Journal, Professor John Hart

Ely criticized Roe as a decision which "is not constitutional law

and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be." Ely added: "What

is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not

inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers’ thinking

respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the

provisions they included, or the nation’s governmental structure."

Professor Laurence Tribe had similar thoughts: "One of the most curious

things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the

substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found." Liberal

law professors Alan Dershowitz, Cass

Sunstein, and Kermit Roosevelt have also expressed

disappointment with Roe.

Jeffrey

Rosen and Michael Kinsley echo Ginsburg, arguing that a legislative approach

movement would have been the correct way to build a more durable consensus in

support of abortion rights. William Saletan wrote that "Blackmun’s

[Supreme Court] papers vindicate every indictment of Roe: invention,

overreach, arbitrariness, textual indifference." Benjamin Wittes has

written that Roe "disenfranchised millions of conservatives on an

issue about which they care deeply". And Edward Lazarus, a former Blackmun

clerk who "loved Roe’s author like a grandfather" wrote: "As a

matter of constitutional interpretation and judicial method, Roe borders

on the indefensible....Justice Blackmun’s opinion provides essentially no

reasoning in support of its holding. And in the almost 30 years since Roe’s

announcement, no one has produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own

terms."

The

assertion that the Supreme Court was making a legislative decision is often

repeated by opponents of the Court's decision. The "viability"

criterion, which Blackmun acknowledged was arbitrary, is still in effect,

although the point of viability has changed as medical science has found ways

to help premature babies survive.

Public

opinion

A

Gallup

poll conducted in May 2009 indicates that a minority of Americans, 37%,

believe that abortion should be legal in any or most circumstances, compared to

41% in May 2008. Similarly, an April 2009 Pew Research Center poll showed a softening of

support for legal abortion compared to the previous years of polling. People

who said they support abortion in all or most cases dropped from 54% in 2008 to

46% in 2009.

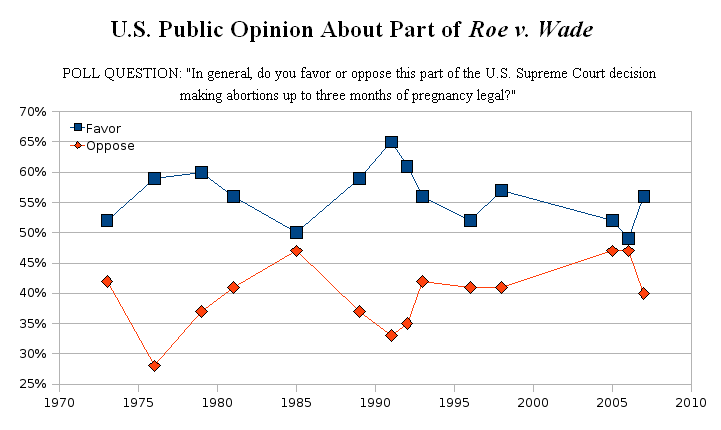

In

contrast, an October 2007 Harris poll on Roe v. Wade asked the following

question:

In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that states laws which made it illegal for a woman to have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy were unconstitutional, and that the decision on whether a woman should have an abortion up to three months of pregnancy should be left to the woman and her doctor to decide. In general, do you favor or oppose this part of the U.S. Supreme Court decision making abortions up to three months of pregnancy legal?

In

reply, 56 percent of respondents indicated favour while 40 percent indicated

opposition. The Harris organization concluded from this poll that "56

percent now favours the U.S. Supreme Court decision." Pro-life activists

have disputed whether the Harris poll question is a valid measure of public

opinion about Roe's overall decision, because the question focuses only

on the first three months of pregnancy. The Harris poll has tracked public

opinion about Roe since 1973:

|

|

Graph showing public support for Roe v. Wade

over the years

|

Regarding

the Roe decision as a whole, more Americans support it than support

overturning it. When pollsters describe various regulations that Roe

prevents legislatures from enacting, support for Roe drops.

Role

in subsequent decisions and politics

Opposition

to Roe on the bench grew when President Reagan—who supported legislative

restrictions on abortion—began making federal judicial appointments in 1981.

Reagan denied that there was any litmus test: "I have never given a litmus

test to anyone that I have appointed to the bench…. I feel very strongly about

those social issues, but I also place my confidence in the fact that the one

thing that I do seek are judges that will interpret the law and not write the

law. We've had too many examples in recent years of courts and judges

legislating."

In

addition to White and Rehnquist, Reagan appointee Sandra Day O'Connor began

dissenting from the Court's abortion cases, arguing in 1983 that the

trimester-based analysis devised by the Roe Court was

"unworkable." Shortly before his retirement from the bench, Chief

Justice Warren Burger suggested in 1986 that Roe be

"reexamined"; the associate justice who filled Burger's place on the

Court—Justice Antonin Scalia—vigorously opposed Roe. Concern about

overturning Roe played a major role in the defeat of Robert Bork's

nomination to the Court in 1987; the man eventually appointed to replace Roe-supporter

Lewis Powell was Anthony M. Kennedy.

The

Supreme Court of Canada used the rulings in both Roe and Doe v.

Bolton as grounds to find Canada's federal law restricting access to

abortions unconstitutional. That Canadian case, R.

v. Morgentaler, was decided in 1988.

Webster

v. Reproductive Health Services

Main

article: Webster v. Reproductive Health

Services

In

a 5–4 decision in 1989's Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, Chief

Justice Rehnquist, writing for the Court, declined to explicitly overrule Roe,

because "none of the challenged provisions of the Missouri Act properly

before us conflict with the Constitution." In this case, the Court upheld

several abortion restrictions, and modified the Roe trimester framework.

In

concurring opinions, O'Connor refused to reconsider Roe, and Justice

Antonin Scalia criticized the Court and O'Connor for not overruling Roe.

Blackmun – author of the Roe opinion – stated in his dissent that White,

Kennedy and Rehnquist were "callous" and "deceptive," that

they deserved to be charged with "cowardice and illegitimacy," and

that their plurality opinion "foments disregard for the law." White

had recently opined that the majority reasoning in Roe v. Wade was

"warped."

Planned

Parenthood v. Casey

Main

article: Planned Parenthood v. Casey

During

initial deliberations for Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992),

an initial majority of five Justices (Rehnquist, White, Scalia, Kennedy, and

Thomas) were willing to effectively overturn Roe. Kennedy changed his

mind after the initial conference, and O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter joined

Blackmun and Stevens to reaffirm the central holding of Roe, saying,

"At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of

existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life."

Only Justice Blackmun would have retained Roe entirely and struck down

all aspects of the statute at issue in Casey.

Scalia's

dissent acknowledged that abortion rights are of "great importance to many

women", but asserted that it is not a liberty protected by the

Constitution, because the Constitution does not mention it, and because

longstanding traditions have permitted it to be legally proscribed. Scalia

concluded: "[B]y foreclosing all democratic outlet for the deep passions

this issue arouses, by banishing the issue from the political forum that gives

all participants, even the losers, the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an

honest fight, by continuing the imposition of a rigid national rule instead of

allowing for regional differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies

the anguish."

Stenberg

v. Carhart

Main

article: Stenberg v. Carhart

During

the 1990s, the state of Nebraska attempted to ban a certain second-trimester

abortion procedure known as intact dilation and extraction (sometimes called

partial birth abortion). The Nebraska ban allowed other second-trimester

abortion procedures called dilation and evacuation abortions. Ginsburg (who

replaced White) stated, "this law does not save any fetus from

destruction, for it targets only 'a method of performing abortion'." The

Supreme Court struck down the Nebraska ban by a 5–4 vote in Stenberg v.

Carhart (2000), citing a right to use the safest method of second trimester

abortion.

Kennedy,

who had co-authored the 5-4 Casey decision upholding Roe, was

among the dissenters in Stenberg, writing that Nebraska had done nothing

unconstitutional. Kennedy described the second trimester abortion procedure

that Nebraska was not seeking to prohibit: "The fetus, in many

cases, dies just as a human adult or child would: It bleeds to death as it is

torn from limb from limb. The fetus can be alive at the beginning of the

dismemberment process and can survive for a time while its limbs are being torn

off." Kennedy wrote that since this dilation and evacuation procedure

remained available in Nebraska, the state was free to ban the other procedure

sometimes called "partial birth abortion."

The

remaining three dissenters in Stenberg – Thomas, Scalia, and

Rehnquist – disagreed again with Roe: "Although a State may

permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do

so."

Gonzales

v. Carhart

Main

article: Gonzales v. Carhart

In

2003, Congress passed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which led to a

lawsuit in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart. The Court had previously

ruled in Stenberg v. Carhart that a state's ban on "partial birth

abortion" was unconstitutional because such a ban would not allow for the

health of the woman. The membership of the Court changed after Stenberg,

with John Roberts and Samuel Alito replacing Rehnquist and O'Connor, respectively.

Further, the ban at issue in Gonzales v. Carhart was a clear federal

statute, rather than a relatively vague state statute as in the Stenberg

case.

On

April 18, 2007, the Supreme Court handed down a 5 to 4 decision upholding the

constitutionality of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act. Kennedy wrote the

majority opinion, asserting that Congress was within its power to generally ban

the procedure, although the Court left the door open for as-applied challenges.

Kennedy's opinion did not reach the question whether the Court's prior

decisions in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Stenberg

v. Carhart were valid, and instead the Court said that the challenged

statute is consistent with those prior decisions whether or not those prior

decisions were valid.

Joining

the majority were Chief Justice John Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito.

Ginsburg and the other three justices dissented, contending that the ruling

ignored Supreme Court abortion precedent, and also offering an equality-based

justification for that abortion precedent. Thomas filed a concurring opinion,

joined by Scalia, contending that the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade

and Planned Parenthood v. Casey should be reversed, and also noting that

the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act may exceed the powers of Congress under the

Commerce Clause.

Activities

of Norma McCorvey

Norma

McCorvey became a member of the pro-life movement in 1995; she now supports

making abortion illegal. In 1998, she testified to Congress:

It was my pseudonym, Jane Roe, which had been used to create the "right" to abortion out of legal thin air. But Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee never told me that what I was signing would allow women to come up to me 15, 20 years later and say, "Thank you for allowing me to have my five or six abortions. Without you, it wouldn't have been possible." Sarah never mentioned women using abortions as a form of birth control. We talked about truly desperate and needy women, not women already wearing maternity clothes.

As

a party to the original litigation, she sought to reopen the case in U.S.

District Court in Texas to have Roe v. Wade overturned. However, the

Fifth Circuit decided that her case was moot, in McCorvey v. Hill. In a

concurring opinion, Judge Edith Jones agreed that McCorvey was raising

legitimate questions about emotional and other harm suffered by women who have

had abortions, about increased resources available for the care of unwanted

children, and about new scientific understanding of fetal development, but

Jones said she was compelled to agree that the case was moot. On February 22,

2005, the Supreme Court refused to grant a writ of certiorari, and McCorvey's

appeal ended.

Presidential

positions

President

Richard Nixon did not publicly comment about the decision. In private

conversation later revealed as part of the Nixon tapes, Nixon said "There

are times when an abortion is necessary, I know that. When you have a black and

a white" (a reference to interracial pregnancies) "or a rape."

However, Nixon was also concerned that greater access to abortions would foster

"permissiveness," and said that "it breaks the family."

Generally,

presidential opinion has been split between major party lines. The Roe

decision was opposed by Presidents Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George W.

Bush. President George H.W. Bush also opposed Roe, though he had

supported abortion rights earlier in his career.

President

Jimmy Carter supported legal abortion from an early point in his political

career, in order to prevent birth defects and in other extreme cases; he

encouraged the outcome in Roe and generally supported abortion rights. Roe

was also supported by President Bill Clinton. President Barack Obama has taken

the position that "Abortions should be legally available in accordance

with Roe v. Wade."

|

|

Guttmacher Institute Chart of abortion

restrictions transcribed from original here.

|

State

laws regarding Roe

Several

states have enacted so-called trigger laws which would take effect in the event

that Roe v. Wade is overturned. Those states include Arkansas, Illinois,

Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota and South Dakota. Additionally,

many states did not repeal pre-1973 statutes that criminalized abortion, and

some of those statutes could again be in force if Roe were reversed.

Other

states have passed laws to maintain the legality of abortion if Roe v. Wade

is overturned. Those states include California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine,

Maryland, Nevada and Washington.

The

Mississippi Legislature has attempted to make abortion infeasible without

having to overturn Roe v. Wade. However the law is currently being challenged

in Federal courts and has been temporarily blocked.

INTERNET SOURCE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doe_v._Bolton

Argued December 13,

1971

Reargued October 11, 1972 Decided January 22, 1973 |

|||||||

Full case name

|

‘Mary Doe’

v. Arthur K. Bolton, Attorney General of Georgia, et al. |

||||||

Citations

|

|||||||

Holding

|

|||||||

The three

procedural conditions in 26-1202 (b) of Ga. Criminal Code violate the Fourteenth

Amendment.

|

|||||||

Court membership

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

Case opinions

|

|||||||

Majority

|

Blackmun, joined by Burger, Douglas,

Brennan, Stewart, Marshall, Powell

|

||||||

Concurrence

|

Burger

|

||||||

Concurrence

|

Douglas

|

||||||

Dissent

|

White, joined by Rehnquist

|

||||||

Dissent

|

Rehnquist

|

||||||

Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973), was a

decision of the United States Supreme Court overturning the abortion law of

Georgia. The Supreme Court's decision was released on January 22, 1973, the

same day as the decision in the better-known case of Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

History

of case during the 1970s

The

Georgia law in question permitted abortion only in cases of rape, severe fetal

deformity, or the possibility of severe or fatal injury to the mother. Other

restrictions included the requirement that the procedure be approved in writing

by three physicians and by a special committee of the staff of the hospital

where the abortion was to be performed. In addition, only Georgia residents

could receive abortions under this statutory scheme: non-residents could not

have an abortion in Georgia under any circumstances.

The

plaintiff, a pregnant woman who was given the pseudonym "Mary Doe" in

court papers to protect her identity, sued Arthur K. Bolton, then the Attorney

General of Georgia, as the official responsible for enforcing the law. The

anonymous plaintiff has since been identified as Sandra Cano, a 22-year-old

mother of three who was nine weeks pregnant at the time the lawsuit was filed.

Cano describes herself as pro-life and claims her attorney, Margie Pitts Hames,

lied to her in order to have a plaintiff.

A

three-judge panel of the United States district court declared the conditional

restrictions portion of the law unconstitutional, but upheld the medical

approval and residency requirements, and refused to issue an injunction against

enforcement of the law. The plaintiff appealed to the Supreme Court under a

statute, since repealed, permitting bypass of the circuit appeals court.

The

oral arguments and re-arguments followed the same schedule as those in Roe.

Atlanta attorney Hames represented Doe at the hearings, while Georgia assistant

attorney general Dorothy Toth Beasley represented Bolton.

The

same 7-2 majority (Justices White and Rehnquist dissenting) that struck down a

Texas abortion law in Roe v. Wade, invalidated most of the remaining

restrictions of the Georgia abortion law, including the medical approval and

residency requirements. Together, Doe and Roe declared abortion

as a constitutional right and by implication overturned most laws against

abortion in other US states.

Broad

definition of health

The

Court's opinion in Doe v. Bolton stated that a woman may obtain an

abortion after viability, if necessary to protect her health. The Court defined

"health" as follows:

Whether, in the words of the Georgia statute, "an abortion is necessary" is a professional judgment that the Georgia physician will be called upon to make routinely. We agree with the District Court, 319 F. Supp., at 1058, that the medical judgment may be exercised in the light of all factors - physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman's age - relevant to the well-being of the patient. All these factors may relate to health.

Litigation

30 years later

In

2003, Sandra Cano filed a motion to re-open the case claiming that she had not

been aware that the case had been filed on her behalf and that if she had known

she would not have supported the litigation. The district court denied her

motion, and she appealed. When the appeals court also denied her motion, she

requested review by the United States Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court

declined to hear Sandra Cano's suit to overturn the ruling.

No comments:

Post a Comment